On February 4, 2008, millions of Colombians stepped out to thMillions March in Bogotá e streets to protest against the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC). In Bogotá some streets were abandoned as it seemed the entire population gathered in designated intersections waving placards and banners. In all, about 2 million people came together in Bogotá, and millions more in over 125 cities around the world. The global media descended on the march attracted to its magnitude (some call it the largest demonstration in Colombia’s history) and its origins as a Facebook group started by a young Colombian engineer with no affiliation to parties or civil-sector organizations.

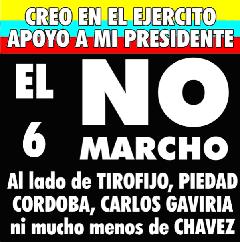

But the march was actually a lot more politicized and controversial than it appeared to be at first glance. In fact, it has led to a significant counter-movement propelled by the country’s longstanding human rights and victims’ groups such as the Movimiento Nacional de Víctimas de Crímenes de Estado, Indepaz, and Redepaz, which are now calling for a march in support of the victims of paramilitarism and the state, to be held on March 6. It is already evident that this “counter-march” will not count with the support or participation of the millions of Colombians that came out on February 4. While many are interpreting the February 4 march as a testament to Colombians’ resolve to end the conflict, a more adequate interpretation would see it as a powerful extension of the conflict: as a weapon being used by one side against the other. The lack of support for March 6 will be a reminder of how far Colombians are from clamoring for peace, and in effect how far Colombia actually remains from peace.

The February 4 march was organized in reaction to events in December and January, when the FARC liberated hostages to President Chávez in Venezuela in an attempt to exclude the Uribe government and gain political power for themselves and for President Chávez. Even though the organizers of the march organized it as against the FARC – but not necessarily pro-government – many interpreted the march as a vow of support for President Uribe. In fact, the Partido de la U (a pro-Uribe party) announced within a few days of the demonstration that this is the right moment to consider amending the Constitution once again in order to allow President Uribe to run for a third time for office.

The supporters of the President were able to interpret the march in this way because, unlike the mass marches for peace in 1997 and the ones against kidnappings in 1999, this one was in line with the government’s rhetoric and agenda in criticizing the FARC while turning a blind eye toward the paramilitaries and state crimes. At the march I attended in front of the United Nations in New York, there were no specific pro-Uribe posters, but there was little tolerance for alternative views. One demonstrator who held a sign stating, “I want to forget guns- I want to know education” was harassed by other participants for not having a clear message against the FARC. The representatives from the Polo Democratico (the leftist opposition party) felt the need to stand apart from everyone else, as they held signs protesting the violence committed by the paramilitary groups and the government – those crimes which the official march was ignoring.

The February 4 march was so one-sided that even the government saw it in its interest to support it. Though The Economist states that “the government cleverly stayed out of” the organization of the February 4 march, the Colombian consulates’ e-mail distribution lists were key in organizing the international marches and Colombian embassies around the world have since posted photos of the event (See the Embassy in Sweden and the Consulate in Australia) .

And the government’s reactions to the March 6 event have been quite the opposite. Last week, presidential adviser José Obdulio Gaviria stated that he would not attend on March 6, explaining that “it will be difficult for Colombian society to participate in this type of event, when we just finished marching against the people who are convening it,” implying that the victims’ movements convening the march are part of the FARC (as was also argued in a recent op-ed piece in El Tiempo). To even further complicate the march, the FARC did recently announce their support for the march on their website (and the paramilitary leader Salvatore Mancuso had announced on his website his support for the February 4 march). Calling individuals and organizations guerrilla members is an intimidation tool that has been used in the past by the government against the opposition, and has often led to death threats—not necessarily from the government, but from government supporters radical enough to take all steps necessary to defend the president’s image. In fact, the organizers have been receiving death threats during the past week (some of them signed by the new paramilitary groups that trace their origin to the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC)).

The February 4 march was supposed to be a call against violence in Colombia, but because it took a stance against one side of the conflict, in essence ignoring the crimes committed by the state and paramilitaries responsible for the majority of human rights violations in Colombia, it took a side of the conflict.

There may have been good reasons to have a march against the FARC instead of against violence in Colombia in general. The demonstration may have taken a hit on the morale of the FARC’s fighters and may encourage more of them to turn themselves in and demobilize in 2008. Anyone who thought the FARC had the support of the Colombian population now has to question his or her belief.

But there were better reasons to have one large march for peace against all types of violence, instead of a march against the FARC, or even multiple marches against each of the violent factions involved in the conflict. First of all, a march for peace in Colombia would have joined the various sides of a victimized country. It would have helped resolve differences, instead of driving the wedge even deeper between Colombians. It would have shown Colombians and the world that, even through we may have different views, we all believe it is time to stop the violence.

So why won’t the millions of Colombians from February 4 come out to the streets to protest against state and paramilitary violence? To some extent, the lack of support for the March 6 event is a reflection of the popularity of the Uribe government, which has been fighting the FARC while negotiating with the paramilitaries. However, it is also a sad reflection of a belief held by many Colombians: that violence and human rights violations against civilians are at times justifiable in the Colombian conflict. This belief, best described by Michael Taussig in “Law in a Lawless Land,” (and also discussed by Rodrigo Pardo, Director of Revista Cambio, in a recent El Tiempo blog) I believe goes a long way in explaining the lack of support for a march against the country’s greatest human rights violator. It demonstrates that on February 4 Colombians rallied for one side of the conflict, not for an end to it. It demonstrates that much work is still needed to bring Colombian society to a peaceful solution to the conflict.

(2/20 Addendum: Check out the recent op-ed piece about the March 6 march in El Tiempo by Camilo Gonzalez Posso, President of Indepaz. He argues that the march is pushing the debate in Colombia on whether the state is responsible for crimes. Scroll down to the comments to see at least two of them stating that the FARC is behind the march and at least one of them calling Gonzalez a liar. Once again, this is just to show how far Colombians are from accepting the responsibility of all sides in the conflict, and how far they are from simply clamoring for peace, instead of just attacking the other side.)

Reply