by Michael Bustamante and Elizabeth Jordan

Since assuming the interim presidency of Cuba in July 2006, Raul Castro has drawn much attention for encouraging Cuban citizens to voice their opinions and even criticize government officials. In a critical speech on July 26, 2007 – a national holiday commemorating the launching of the Cuban Revolution – Fidel’s younger, supposedly more pragmatic brother seemed to contribute to this process of collective introspection, admitting that Cuban workers were underpaid and that “structural” reforms in the economy were necessary.

The speech came hand in hand with a series of community meetings held throughout the island during the course of 2007. For months now, second-hand reports of the proceedings have been run in the press. The story seems to be that over time, ordinary Cubans, long privately critical of the government but reluctant to publicly voice their concerns, have grown bolder in blaming authorities for economic shortages and a host of other problems. Back in late 2006, Raul even went so far as to say that students should debate “fearlessly,” and it seems they have taken him up on the offer.

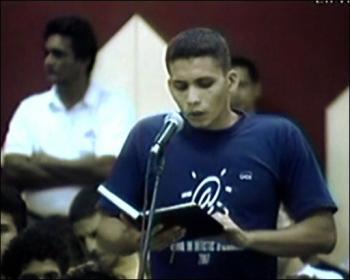

Last week, a video surfaced on BBC Mundo of two students at Havana’s Universidad de Ciencias Informaticas (UCI) asking tough questions of National Assembly President Ricardo Alarcón at a January 19, 2008 forum. The interchange, as originally viewed in the clip made available by BBC Mundo, is striking for several reasons.

Above all, the questions are pointed and poignant. One student, 21-year-old Eliecer Avila, blasts limitations on Cubans’ freedom to travel, lamenting that if he wanted to bring his entire family to Bolivia to pay their respects at the place where Che Guevara fell in battle, he would not be able to do so (a statement that could either reflect his revolutionary fervor or be a keen rhetorical strategy). Next, he turns to a strident critique of Cuba’s confusing dual-currency economy. Why, he implores, are Cuba’s workers paid in nearly-valueless moneda nacional, when many necessities are only available in peso convertible – a form of “monopoly money” used in the tourist sector and pegged to the U.S. dollar that is worthless on international exchange markets, but nonetheless possesses 25 times more “poder adquisitivo” (purchasing power) within the Cuban economy? The second student, Rafael Alejandro Hernández, asks sarcastically why he should vote for National Assembly candidates who never visit his university or speak with their supposed constituents, let alone formulate clear proposals or plans of action.

The answers Alarcón provides are evasive and at times nonsensical – a stark contrast to his normally well-prepared and eloquent officialist jargon. In response to the travel question, Alarcón said simply, “Well, if everyone could travel any time they wanted, you can’t imagine the traffic-jam there would be in the skies.”

As the video shot around the internet and made its way to the Cuban-American blogosphere, Avila was heralded as a hero and an activist. The rhetoric only became more dramatic when it appeared he had been arrested, presumably as retribution for his comments.

A few days later, however, Avila was seen on another video, this time one produced by CubaDebate, a government-run program from Havana. In this video, a somewhat nervous and less brazen Avila is seated next to the slick and influential President of the Federación Estudiantil Universitaria (FEU), who is coincidentally the son of Cuban Vice-President Carlos Lage. Avila disputes the claim that he was arrested, explaining that he was actually just given a lift to see a doctor. Any questions or inquietudes that might have been posed during the forum, he insists, were intended to better socialism in Cuba, not undermine it. Hernández, the second student featured in the original BBC clips, also appeared in this video to “clarify” his comments.

Now, yet another wrench has been thrown in the story. As voices began to criticize Cuban authorities for manipulating these students and forcing them to “retract” or “reframe” their original comments, the Cuban government has released the entire hour-long video of the encuentro with Alarcón.

On one hand, the full-length video confirms that the BBC took the students’ remarks at least partially out of context. Eliminated from the original clips were the ten plus minutes of opening remarks in which both Eliecer and Rafael do in fact openly express their support for socialism and portray their questions as fully in line with “revolutionary” thinking. In other words, the BBC only featured those pieces of video in which the students seemed to most stridently challenge authorities – a natural choice for headline-hungry reporters, but one which perhaps made the exchange with Alarcón seem more confrontational than it really was.

On the other hand, this fuller context may be irrelevant. Whether the students are true believers in some vision of an improved, more just, and more democratic socialism, or whether their long-winded reflections aligning themselves with “the revolution” were but a necessary preface to cushion the power of their later comments, the implications are clear. Long-stifled criticism in Cuba is starting to edge its way into the public sphere. Feelings once only expressed in the privacy of one’s own home are coming out into the open. This is not to say the government should be commended necessarily for its renewed spirit of openness. This “openness” comes, of course, with strict limitations; certain topics or manners of speaking remain taboo. But as an editorial in the South Florida Sun-Sentinel points out, Cubans are taking advantage of a space that has been offered to them by the island’s leadership, and their expectations have been raised as a result, leaving authorities with no choice but to respond.

Contrary to some reporting, the anxieties Cubans have expressed in these forums are not only economic. Yes, many have spoken out against the dual-currency system, so-called “tourist-apartheid,” shortages of goods – tensions that theoretically could be relieved were the government to adopt some form of Vietnamese or Chinese style “market socialism” in the future (or if Cuba were to successfully develop its energy resources – post on this coming soon).

But when students like Eliecer and Rafael urge representatives of Cuba’s National Assembly, Council of Ministers, and other government officials to have greater contact with the people, they are clearly suggesting that they do not truly feel represented. At a fundamental level, they are acknowledging that their interests do not have an official voice.

Even if Eliecer and his classmates today believe that Cuba’s one-party socialism can be made more democratic, more responsive to people’s needs, in the end their hopes may very well hit a wall of distrust, disillusionment, and disappointment, irrespective of the government’s ability to provide greater economic well-being to the population. For in the long-run, without greater electoral competition, the incentives for Cuban politicians to actually listen and respond to the concerns of their constituents remain limited. After all, they are not perfect incarnations of Che Guevara’s Hombre Nuevo, but are human, with the same vices and instincts toward self-preservation that inhibit us all.

The true course of events surrounding these multiple videos will probably never come to light. And the innermost thoughts and intentions of these students will also remain a mystery. But even if Eliecer and Rafael haven’t abandoned their faith in Cuba’s socialist system, their remarks may nonetheless represent the seeds of doubt necessary for greater change in the future. That is our hope.

Reply